Illness tied to heat, pathogens and toxins is a lethal threat that countries are ill-prepared to confront. Ground zero for this new era, Pakistan, provides a look at what the future holds elsewhere.

Sanam, 24, with her son Naveed at a center where underweight babies are kept with their mothers. Muhammad Yaqoob stood on his concrete porch and watched the black, angry water swirl around the acacia trees and rush toward his village last September, the deluge making a sound that was like nothing he had ever heard. “It was like thousands of snakes sighing all at once,” he recalled.

Pakistan is the epicenter of a new global wave of disease and death linked to climate change, according to a Washington Post analysis of climate data, leading scientific studies, interviews with experts and reporting from some of the places bearing the brunt of Earth’s heating.

The results show how the risk has been growing and will escalate into the future. The number of people exposed to a month of highly dangerous heat, even in the shade, will be four times higher in 2030 than at the turn of the millennium. So far this year, more than 235,000 Peruvians have come down with dengue fever and at least 399 died, according to Peru’s national center for disease control, the most in that nation’s history. Smoke from record-breaking Canadian wildfires billowed across the United States, triggering asthma attacks that forced hundreds to seek hospital care.

Last year in Pakistan, dangers piled one atop the other. First, the country suffered a record-breaking heat wave beginning in March. Fires rampaged through its forests. Record high temperatures melted glaciers faster than normal, triggering flash floods. And then heavy monsoon rains caused unprecedented floods, which left 1,700 dead, swept away 2 million homes and destroyed 13 percent of the country’s health-care system.

The proliferation of climate ills has taxed this regional hospital center at the same time it has taken in patients from 12 nearby clinics and medical dispensaries swept away in the flood, he said.The hospital has taken a variety of “special measures” to support the heat patients, including creating the small stroke unit, where patients are treated before either being admitted or sent home with electrolyte powder packets for rehydration.

“Miscarriages have been increasing because of the intense heat,” said Zainab Hingoro, a local health-care worker. When she once would have 3 out of 10 pregnant patients miscarry, she now has 5 to 6 out of 10. The number of low-birth-weight babies is “drastically increasing,” she added. After the floods, Pakistan grappled with over 3 million suspected malaria cases, up from 2.6 million in 2021, according to the World Health Organization. The outbreak was spurred on by standing water and other circumstances making it easier for mosquitoes to breed, reversing decades of progress of reducing cases.

But three months of living surrounded by contaminated water that smelled like the corpses of dead animals took its toll. First, one of his neighbors sparked a fever, then another. Getting sick in Bagh Yusuf was never easy, even before the flood. Villagers go to a small dispensary if they fall ill: A private doctor costs too much and a trip to the hospital is a last resort.He was overcome with a fever stronger than he had ever experienced and began bleeding from his nose.

The air around his workspace outside a downtown restaurant is always several degrees hotter than the normal air temperature, Dil Murad said, which can often be overwhelming. He said he feels trapped in his job as the summer heat intensifies, and tries to keep as cool as he can by drinking large amounts of water every hour.

Sweaty rickshaw drivers and construction workers crowd around volunteers passing out cooling herbal drinks made of the bluish-red falsa berries, and residents buy blocks of ice from the area’s busy ice factories to keep themselves - and their food - cool.In villages outside the city, farmworkers still venture into the rice, wheat and fodder fields, but try to rest during the hottest part of the day, from noon until about 3 p.m. Even then, some become dizzy and collapse.

But residents have said that they have done little to help them during the hottest days. The district had no permanent heat stroke center until the height of the heat wave last May, when a local NGO, the Community Development Foundation, helped establish one in a local hospital. It has only eight beds.

“The way the rich countries are going to respond is by spending more to protect ourselves, and in many parts of the world those opportunities don’t exist,” said Michael Greenstone, a University of Chicago economist and the study’s co-author. If the air is too moist to absorb sweat, a person’s internal body temperature will continue to rise. The heart pumps faster and blood vessels expand to move more blood closer to the skin, in order cool off. At the same time, the brain sends a signal to send less blood to the kidneys to stop losing liquid through urine, which deprives the kidneys of oxygen.

Temperatures had reached 122 degrees one day in Pir Bux Bhatti during last year’s heat wave when Fazeela Mumtaz Bhatti, age 46, rose to prepare breakfast for her husband, Mumtaz Ali, 50, and their 11 children. Naheed mourns the loss of her mother, who often spoke of finding Naheed a good man to marry, and used to tease her eldest daughter by saying, “You are only a guest here, you only have so much time to live in your father’s house.” In quieter moments, she would tell Naheed, “You have to find courage within yourself because life is difficult.”“We just couldn’t keep her safe and alive,” she said quietly. “It’s difficult for me, but I have to take care of my brothers and sisters.

Pakistan - a fast-growing country of 241 million - had myriad challenges even before the floods, with a high percentage of poverty, low literacy rate, vanishing water supply, rising inflation and ongoing political turmoil after last year’s ouster of former prime minister Imran Khan, now jailed, with elections set for the coming months.

Muhammad Jaohar Khan, a health specialist with UNICEF in Islamabad, said that the floods - which submerged more than 2,000 health-care facilities - ratcheted up pressure on a system that was already burdened and failing to reach the poor in rural provinces like Sindh. Even before the floods, poor nutrition had stunted the growth of 40 percent of the children under 5 in Pakistan.

At the Jacobabad Institute of Medical Sciences, Kamala Bakht, a doctor in the infant nutrition center, said that the number of low birth weight babies entering the feeding program had been steadily increasing since 2018 - from about 40 to 55 a month.

Australia Latest News, Australia Headlines

Similar News:You can also read news stories similar to this one that we have collected from other news sources.

- Climate change, inflation, Dallas climate plan, smilingLetters to the Editor

- Climate change, inflation, Dallas climate plan, smilingLetters to the Editor

Read more »

Climate Activists and Frontline communities Call for Genuine Climate Leadership From African Leaders as Climate Summit Kicks OffAs the Africa climate summit begins in Nairobi this week, grassroots groups and climate activists from across the continent will be holding African leaders to account to deliver concrete climate action and plans to address the continent’s pressing needs. “ We are calling on African governments to pr...

Climate Activists and Frontline communities Call for Genuine Climate Leadership From African Leaders as Climate Summit Kicks OffAs the Africa climate summit begins in Nairobi this week, grassroots groups and climate activists from across the continent will be holding African leaders to account to deliver concrete climate action and plans to address the continent’s pressing needs. “ We are calling on African governments to pr...

Read more »

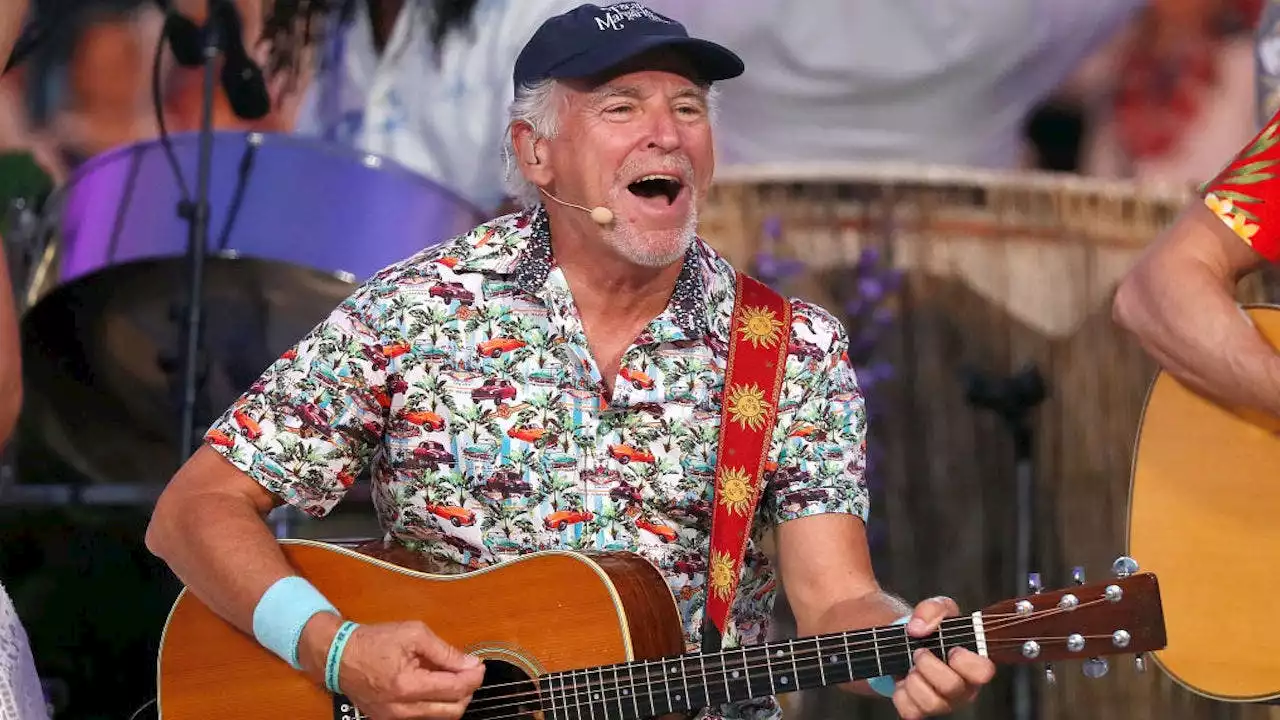

Merkel cell carcinoma, the disease that killed Jimmy Buffett: What to know about this illnessMusic icon Jimmy Buffett passed away on Friday from merkel cell carcinoma, a disease he had been fighting for four years. Here's what you should know about the rare but aggressive form of skin cancer.

Merkel cell carcinoma, the disease that killed Jimmy Buffett: What to know about this illnessMusic icon Jimmy Buffett passed away on Friday from merkel cell carcinoma, a disease he had been fighting for four years. Here's what you should know about the rare but aggressive form of skin cancer.

Read more »

Guardians miss opportunity to gain ground in AL Central with 6-2 loss to RaysJosh Naylor delivered an RBI single in his first game back from the injured list.

Guardians miss opportunity to gain ground in AL Central with 6-2 loss to RaysJosh Naylor delivered an RBI single in his first game back from the injured list.

Read more »

Higher Ground: Pope ignites furyWelcome to Higher Ground, the newsletter and website dedicated to helping families of faith navigate a chaotic world with rigorous reporting, commentary and analysis on national, global and cultural issues, with reporting from the experienced journalists of The Washington Times.

Higher Ground: Pope ignites furyWelcome to Higher Ground, the newsletter and website dedicated to helping families of faith navigate a chaotic world with rigorous reporting, commentary and analysis on national, global and cultural issues, with reporting from the experienced journalists of The Washington Times.

Read more »

CBS NY medical correspondent Dr. Max Gomez dies after long illness“Dr. Max was just one of those guys that every time you saw him you immediately identified him not only as Dr. Max but CBS 2’s Dr. Max.”

CBS NY medical correspondent Dr. Max Gomez dies after long illness“Dr. Max was just one of those guys that every time you saw him you immediately identified him not only as Dr. Max but CBS 2’s Dr. Max.”

Read more »